Windows x64 Shellcode

Recently I have been rewriting several pieces of shellcode that I have implemented for x86 Windows into x64 and have had a hard time finding resources online that aided in my endeavors. I wanted to write a blog post (my first one) in order to hopefully help someone that is or will be in the position that I was in while trying to port over shellcode.

There are already several tutorials out on the internet that help in beginning to learn shellcode and I am not going to go over that. I not going to touch much on the basics of assembly, although I will talk about calling conventions, register clobbering and registers.

Refer to papers such as Skape’s Understanding Windows Shell code. or resources like project-shellcode for in-depth shellcode writing tutorials.

I will go over the differences between 32 and 64 bit assembly that I have noticed and how to work with them as well as some of the structures windows uses that are useful to know about for shellcode in the 64bit environment. I will also introduce two tools that I have created in helping my exploit development process.

Lastly before I get started I want to mention that I am still in the somewhat beginning stages of exploitation development and for the purpose of this tutorial I am only going to rely on needing to target Windows 7 x64 machines. I am also going to use the phrases Win32 to refer to x86 windows builds and Win64 to refer to x64 builds.

Registers

x86

Normally on a x86 processor, there are 8 general purpose registers that are all 32 bits wide.

-

eax - Accumulator register

-

ecx - Counter Register

-

edx - Data Register

-

ebx - Base Register

-

esp - Stack Pointer

-

ebp - Base Pointer

-

esi - Source Index

-

edi - Destination Index

and the instruction pointer . . .

- eip - Instruction Pointer

Because of backwards compatibility reasons, 4 of those registers {eax. ebx, ecx and edx} can be broken down into 16 bit and 8 bit varieties.

-

AX - Low 16 bits of EAX.

-

AH - High 8 bits of AX.

-

AL - Low 8 bits of AX.

-

BX - Low 16 bits of EBX.

-

BH - High 8 bits of EBX

-

BL - Low 8 bits of EBX

The same goes for ECX, and EDX by taking the middle letter (c, d) and post fixing it with (X, H or L)

x64

64 bit processors extended the above 8 registers by prefixing all of them with an “R”.

RAX, RCX, RDX.. etc. It is important to note that all other addressing forms are still the same (eax, ax, al… can still be used).

Also introduced are 8 new registers. r8, r9, r10, r11, r12, r13, r14 and r15. These registers can also be broken down into 32, 16 and 8 bit versions.

-

r# = 64 bit

-

r#d = low 32 bits

-

r#w = low 16 bits

-

r#b = 8 bits

Unfortunately, unlike being able to address the high 8 bits of the low 16 bits in registers such as eax, this is not possible with these extended registers.

Clobber Registers

Clobber registers are registers that can be overwritten in a function (such as those in the Windows API). These registers are volatile and should not be relied on, although can still be used if the API function of interest is tested to see which registers are actually clobbered.

In the Win32 API . . . EAX, ECX and EDX are clobber registers. In the Win64 API . . . RBP, RBX, RDI, RSI, R12, R13, R14 and R15 are not clobber registers, all others are.

RAX and EAX are used to return parameters from a function for both x86 and x64.

Calling Convention

x86

Win32 uses the stdcall calling convection and passes arguments on the stack backwards.

A call to a function foo with the arguments int x and int y

foo(int x, int y)would need to be passed on the stack as such

push y

push xx64

In win64 the calling convention is different and is similar to Win32 fast call as arguments are passed in registers. The first four arguments are passed in RCX, RDX, R8 and R9 respectively with additional arguments stored on the stack. Keep in mind, the registers fill the arguments vector from right to left on a function prototype.

A call to the MessageBox function in the Windows API for example is declared as follows:

int WINAPI MessageBox(

_In_opt_ HWND hWnd,

_In_opt_ LPCTSTR lpText,

_In_opt_ LPCTSTR lpCaption,

_In_ UINT uType

);In the Win64 convention the arguments would be:

r9 = uType

r8 = lpCaption

rdx = lpText

rcx = hWndShellcode

Let’s Get Started

Now that the key differences have been established for Win64 shellcode, let’s write something!

In order to demonstrate the ability to run Win64 shellcode, I am going to pop a MessageBox. Once I have the code base written to display a MessageBox, I will inject the code into calc with a tool I wrote to ensure that it works within another process.

Notes:

I am using NASM for my assembler. Also, for linking Win64 object files I am using golink, written by Jeremy Gordon.

Open your favorite text editor, mine is Notepad++ for windows, and start typing!

Starting

1.) Declare the NASM directives.

bits 64

section .text

global start2.) Set up the stack

start:

sub rsp, 28h ;reserve stack space for called functions

and rsp, 0fffffffffffffff0h ;make sure stack 16-byte aligned 3.) Let’s get the base address of Kernel32.dll.

In order to do this, a difference in the location of the PEB must be discussed.

In Win32, the PEB lives at [fs:30h] whereas in Win64 the PEB is at [gs:60h].

While the PEB struct has changed dramatically,

we only care about the LDR list which can be seen by using the “!peb” command in Windbg.

Notice how in the Windbg output of the PEB, the Ldr.InMemoryOrderModuleList contained kernel32.dll and it was the third entry. This list shows where PE files are in memory (consisting of both executables and dynamically linked libraries).

Ldr.InMemoryOrderModuleList: 00000000002b3150 . 00000000002b87d0

Base TimeStamp Module

ff600000 4a5bc9d4 Jul 13 16:57:08 2009 C:\Windows\System32\calc.exe

77b90000 4ce7c8f9 Nov 20 05:11:21 2010 C:\Windows\SYSTEM32\ntdll.dll

77970000 4ce7c78b Nov 20 05:05:15 2010 C:\Windows\system32\kernel32.dllBy filling the PEB structure in windbg, the location of the Ldr list is determined.

0:000> dt _PEB 000007fffffd4000

ntdll!_PEB

+0x000 InheritedAddressSpace : 0 ''

+0x001 ReadImageFileExecOptions : 0 ''

+0x002 BeingDebugged : 0x1 ''

+0x003 BitField : 0x8 ''

+0x003 ImageUsesLargePages : 0y0

+0x003 IsProtectedProcess : 0y0

+0x003 IsLegacyProcess : 0y0

+0x003 IsImageDynamicallyRelocated : 0y1

+0x003 SkipPatchingUser32Forwarders : 0y0

+0x003 SpareBits : 0y000

+0x008 Mutant : 0xffffffff`ffffffff Void

+0x010 ImageBaseAddress : 0x00000000`ff600000 Void

+0x018 Ldr : 0x00000000`77cc2640 _PEB_LDR_DATALdr is at the 0x18th offset in the PEB.

So far we know that we need to

2.) Go to the LDR list by going to offset 18 in the PEB.

Further going into the LDR list, we need to access the InMemoryOrderModuleList. This is at offset 0x20 in the LDR struct as shown in the below output.

0:000> dt _PEB_LDR_DATA 77cc2640

ntdll!_PEB_LDR_DATA

+0x000 Length : 0x58

+0x004 Initialized : 0x1 ''

+0x008 SsHandle : (null)

+0x010 InLoadOrderModuleList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`002b3140 - 0x00000000`002b87c0 ]

+0x020 InMemoryOrderModuleList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`002b3150 - 0x00000000`002b87d0 ]

+0x030 InInitializationOrderModuleList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`002b3270 - 0x00000000`002b87e0 ]

+0x040 EntryInProgress : (null)

+0x048 ShutdownInProgress : 0 ''

+0x050 ShutdownThreadId : (null)3.) At offset 0x20 is the InMemoryOrderModuleList.

From the figure that had the output of the InMemoryOrderModule list, it is shown that Kernel32.dll is the 3rd entry. The way that the _LIST_ENTRY struct works is as follows and is useful to know so that the base address of Kernel32 can be determined.

0:000> dt _LIST_ENTRY

ntdll!_LIST_ENTRY

+0x000 Flink : Ptr64 _LIST_ENTRY

+0x008 Blink : Ptr64 _LIST_ENTRYThe lists contain a forward and backwards pointer and contains circular references.

In Windbg, !list allows the traversal of these lists. with !list, -x can be used to give a command for each element located. Let’s use that to go to the 0x20th offset in the _PEB_LDR_DATA struct and parse through the _LIST_ENTRY elements.

Will list all of the InMemoryOrderModule list and display the related _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY

0:000> dt _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY

ntdll!_LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY

+0x000 InLoadOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x010 InMemoryOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x020 InInitializationOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x030 DllBase : Ptr64 Void

+0x038 EntryPoint : Ptr64 Void

+0x040 SizeOfImage : Uint4B

+0x048 FullDllName : _UNICODE_STRING

+0x058 BaseDllName : _UNICODE_STRING

+0x068 Flags : Uint4B

+0x06c LoadCount : Uint2B

+0x06e TlsIndex : Uint2B

+0x070 HashLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x070 SectionPointer : Ptr64 Void

+0x078 CheckSum : Uint4B

+0x080 TimeDateStamp : Uint4B

+0x080 LoadedImports : Ptr64 Void

+0x088 EntryPointActivationContext : Ptr64 _ACTIVATION_CONTEXT

+0x090 PatchInformation : Ptr64 Void

+0x098 ForwarderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x0a8 ServiceTagLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x0b8 StaticLinks : _LIST_ENTRY

+0x0c8 ContextInformation : Ptr64 Void

+0x0d0 OriginalBase : Uint8B

+0x0d8 LoadTime : _LARGE_INTEGERNote that in this struct, InLoadOrderLinks points to the next element, DllBase is the base address of the module and FullDllName is the Unicode string of it.

Because we know Kernel32.dll is the 3rd entry in this list, let’s go to it.

0:000> !list -t ntdll!_LIST_ENTRY.Flink -x "dt _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY @$extret" 002b3270

---CUT

ntdll!_LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY

+0x000 InLoadOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`002b3830 - 0x00000000`002b3260 ]

+0x010 InMemoryOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`002b4980 - 0x00000000`002b3840 ]

+0x020 InInitializationOrderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`77970000 - 0x00000000`77985ea0 ]

+0x030 DllBase : 0xbaadf00d`0011f000 Void

+0x038 EntryPoint : 0x00000000`00420040 Void

+0x040 SizeOfImage : 0x2b35c0

+0x048 FullDllName : _UNICODE_STRING "kernel32.dll"

+0x058 BaseDllName : _UNICODE_STRING "ꩀ矌"

+0x068 Flags : 0x77ccaa40

+0x06c LoadCount : 0

+0x06e TlsIndex : 0

+0x070 HashLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xbaadf00d`4ce7c78b - 0x00000000`00000000 ]

+0x070 SectionPointer : 0xbaadf00d`4ce7c78b Void

+0x078 CheckSum : 0

+0x080 TimeDateStamp : 0

+0x080 LoadedImports : (null)

+0x088 EntryPointActivationContext : 0x00000000`002b4d20 _ACTIVATION_CONTEXT

+0x090 PatchInformation : 0x00000000`002b4d20 Void

+0x098 ForwarderLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`002b36e8 - 0x00000000`002b36e8 ]

+0x0a8 ServiceTagLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`002b3980 - 0x00000000`002b3750 ]

+0x0b8 StaticLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0x00000000`77c95124 - 0x00000000`78d20000 ]

+0x0c8 ContextInformation : 0x01d00f7c`80e29f8e Void

+0x0d0 OriginalBase : 0xabababab`abababab

+0x0d8 LoadTime : _LARGE_INTEGER 0xabababab`abababab

---CUTWe now know that the base address of a loaded module is at the 0x30th offset in this list.

So far we know that we need to

1.) Go to the PEB by accessing [gs:60h]

2.) Go to the LDR list by going to offset 18 in the PEB.

3.) At offset 0x20 is the InMemoryOrderModuleList.

4.) At the 3rd element in the InMemoryOrderModuleList is Kernel32 and the 0x30th offset is the base address of the module.

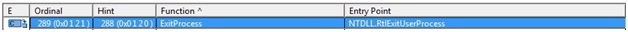

5.) We are going to want to call ExitProcess, which is actually RtlExitUserProcess from ntdll.dll… Ntdll.dll is the 2nd entry in the InMemoryOrderModuleList and I will also grab the base address of it and store it in r15 for later use. I find this method easier and more reliable than relying on Kernel32 to properly execute a function in ntdll.

Output from dependency walker showing that ExitProcess simply points to Ntdll.RtlExitUserProcess.

Now to assembly!

mov r12, [gs:60h] ;peb

mov r12, [r12 + 0x18] ;Peb --> LDR

mov r12, [r12 + 0x20] ;Peb.Ldr.InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov r12, [r12] ;2st entry

mov r15, [r12 + 0x20] ;ntdll.dll base address!

mov r12, [r12] ;3nd entry

mov r12, [r12 + 0x20] ;kernel32.dll base address! We go 20 bytes in here as we are already 10 bytes into the _LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY from the InMemoryOrderModuleList Notice I put Kernel32 into r12, which is not a clobber register! This address needs to be kept for the duration of the execution of the shellcode.

Now that Kernel32 is found, it can be used to load other libraries into ourselves and get the address of processes.

HMODULE WINAPI LoadLibrary(

_In_ LPCTSTR lpFileName

);LoadLibraryA will be used to load a library into ourselves because we cannot rely any dll already being in our target process because shellcode needs to be position independent. In our case user32.dll is going to get loaded.

In order to use the LoadLibraryA function, it must be found in kernel32.dll. . . this is where GetProcAddress comes in.

FARPROC WINAPI GetProcAddress(

_In_ HMODULE hModule,

_In_ LPCSTR lpProcName

);This function takes two arguments, the handle to the module that contains the function we want and the function name.

;find address of loadLibraryA from kernel32.dll which was found above.

mov rdx, 0xec0e4e8e ;lpProcName (loadLibraryA hash from ror13)

mov rcx, r12 ;hModule

call GetProcessAddress Once we know where LoadLibraryA lives, we can use it to load user32.dll.

The “ 0xec0e4e8e” number and following numbers that are moved into rdx before the call to GetProcessAddress are hashed forms of function names.

0xec0e4e8e is LoadLibraryA when each letter is rotated by 13 and added to a sum. This is common in shellcode that I have examined and used in projects such as MetaSploit. I have written a small C program to perform these hashes for me.

#./rot13.exe LoadLibraryA

LoadLibraryA

ROR13 of LoadLibraryA is: 0xec0e4e8eNow load User32.dll

;import user32

lea rcx, [user32_dll]

call rax ;load user32.dll

user_32dll: db 'user32.dll', 0Now we can get the address of the MessageBox function that was described before.

mov rdx, 0xbc4da2a8 ;hash for MessageBoxA from rot13

mov rcx, rax

call GetProcessAddress

and call it

;messageBox

xor r9, r9 ;uType

lea r8, [title_str] ;lpCaptopn

lea rdx, [hello_str] ;lpText

xor rcx, rcx ;hWnd

call rax ;display message box

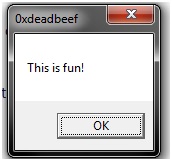

title_str: db '0xdeadbeef', 0

hello_str: db 'This is fun!', 0

and exit the process cleanly with the ExitProcess syscall.

VOID WINAPI ExitProcess(

_In_ UINT uExitCode

);Note that this is the header for the Kernel32 call, but we are going to use RtlExitUserProcess.

;ExitProcess

mov rdx, 0x2d3fcd70

mov rcx, r15 ;base address of ntdll

call GetProcessAddress

xor rcx, rcx ;uExitCode

call rax The finished shellcode with the GetProcAddress function I keep calling:

Note: I have adjusted all of the “lea” instructions with call/pop implementations for the final form. I simply used “lea” above for demonstration.

bits 64

section .text

global start

start:

;get dll base addresses

sub rsp, 28h ;reserve stack space for called functions

and rsp, 0fffffffffffffff0h ;make sure stack 16-byte aligned

mov r12, [gs:60h] ;peb

mov r12, [r12 + 0x18] ;Peb --> LDR

mov r12, [r12 + 0x20] ;Peb.Ldr.InMemoryOrderModuleList

mov r12, [r12] ;2st entry

mov r15, [r12 + 0x20] ;ntdll.dll base address!

mov r12, [r12] ;3nd entry

mov r12, [r12 + 0x20] ;kernel32.dll base address!

;find address of loadLibraryA from kernel32.dll which was found above.

mov rdx, 0xec0e4e8e

mov rcx, r12

call GetProcessAddress

;import user32

jmp getUser32

returnGetUser32:

pop rcx

call rax ;load user32.dll

;get messageBox address

mov rdx, 0xbc4da2a8

mov rcx, rax

call GetProcessAddress

mov rbx, rax

;messageBox

xor r9, r9 ;uType

jmp getText

returnGetText:

pop r8 ;lpCaption

jmp getTitle

returnGetTitle:

pop rdx ;lpTitle

xor rcx, rcx ;hWnd

call rbx ;display message box

;ExitProcess

mov rdx, 0x2d3fcd70

mov rcx, r15

call GetProcessAddress

xor rcx, rcx ;uExitCode

call rax

;get strings

getUser32:

call returnGetUser32

db 'user32.dll'

db 0x00

getTitle:

call returnGetTitle

db 'This is fun!'

db 0x00

getText:

call returnGetText

db '0xdeadbeef'

db 0x00

;Hashing section to resolve a function address

GetProcessAddress:

mov r13, rcx ;base address of dll loaded

mov eax, [r13d + 0x3c] ;skip DOS header and go to PE header

mov r14d, [r13d + eax + 0x88] ;0x88 offset from the PE header is the export table.

add r14d, r13d ;make the export table an absolute base address and put it in r14d.

mov r10d, [r14d + 0x18] ;go into the export table and get the numberOfNames

mov ebx, [r14d + 0x20] ;get the AddressOfNames offset.

add ebx, r13d ;AddressofNames base.

find_function_loop:

jecxz find_function_finished ;if ecx is zero, quit :( nothing found.

dec r10d ;dec ECX by one for the loop until a match/none are found

mov esi, [ebx + r10d * 4] ;get a name to play with from the export table.

add esi, r13d ;esi is now the current name to search on.

find_hashes:

xor edi, edi

xor eax, eax

cld

continue_hashing:

lodsb ;get into al from esi

test al, al ;is the end of string resarched?

jz compute_hash_finished

ror dword edi, 0xd ;ROR13 for hash calculation!

add edi, eax

jmp continue_hashing

compute_hash_finished:

cmp edi, edx ;edx has the function hash

jnz find_function_loop ;didn't match, keep trying!

mov ebx, [r14d + 0x24] ;put the address of the ordinal table and put it in ebx.

add ebx, r13d ;absolute address

xor ecx, ecx ;ensure ecx is 0'd.

mov cx, [ebx + 2 * r10d] ;ordinal = 2 bytes. Get the current ordinal and put it in cx. ECX was our counter for which # we were in.

mov ebx, [r14d + 0x1c] ;extract the address table offset

add ebx, r13d ;put absolute address in EBX.

mov eax, [ebx + 4 * ecx] ;relative address

add eax, r13d

find_function_finished:

ret

For information on the magic of the GetProcAddress function, refer to Skape’s paper.

Now that our shellcode is complete, let’s assemble it and test it.

nasm -f win64 messageBox64bit.asm -o messageBox64bit.obj

golink /console messageBox64bit.obj

./messageBox64bit.exe

This ran our shellcode as a binary.. we want to use it as pure shellcode.

nasm -f bin messageBox64bit.asm -o messageBox64bit.sc

xxd -i messageBox64bit.sc

xxd -i messageBox64bit.sc

unsigned char messageBox64bit_sc[] = {

0x48, 0x83, 0xec, 0x28, 0x48, 0x83, 0xe4, 0xf0, 0x65, 0x4c, 0x8b, 0x24,

0x25, 0x60, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x4d, 0x8b, 0x64, 0x24, 0x18, 0x4d, 0x8b,

0x64, 0x24, 0x20, 0x4d, 0x8b, 0x24, 0x24, 0x4d, 0x8b, 0x7c, 0x24, 0x20,

0x4d, 0x8b, 0x24, 0x24, 0x4d, 0x8b, 0x64, 0x24, 0x20, 0xba, 0x8e, 0x4e,

0x0e, 0xec, 0x4c, 0x89, 0xe1, 0xe8, 0x68, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0xeb, 0x34,

0x59, 0xff, 0xd0, 0xba, 0xa8, 0xa2, 0x4d, 0xbc, 0x48, 0x89, 0xc1, 0xe8,

0x56, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0x89, 0xc3, 0x4d, 0x31, 0xc9, 0xeb, 0x2c,

0x41, 0x58, 0xeb, 0x3a, 0x5a, 0x48, 0x31, 0xc9, 0xff, 0xd3, 0xba, 0x70,

0xcd, 0x3f, 0x2d, 0x4c, 0x89, 0xf9, 0xe8, 0x37, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48,

0x31, 0xc9, 0xff, 0xd0, 0xe8, 0xc7, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x75, 0x73, 0x65,

0x72, 0x33, 0x32, 0x2e, 0x64, 0x6c, 0x6c, 0x00, 0xe8, 0xcf, 0xff, 0xff,

0xff, 0x54, 0x68, 0x69, 0x73, 0x20, 0x69, 0x73, 0x20, 0x66, 0x75, 0x6e,

0x21, 0x00, 0xe8, 0xc1, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0x30, 0x78, 0x64, 0x65, 0x61,

0x64, 0x62, 0x65, 0x65, 0x66, 0x00, 0x49, 0x89, 0xcd, 0x67, 0x41, 0x8b,

0x45, 0x3c, 0x67, 0x45, 0x8b, 0xb4, 0x05, 0x88, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x45,

0x01, 0xee, 0x67, 0x45, 0x8b, 0x56, 0x18, 0x67, 0x41, 0x8b, 0x5e, 0x20,

0x44, 0x01, 0xeb, 0x67, 0xe3, 0x3f, 0x41, 0xff, 0xca, 0x67, 0x42, 0x8b,

0x34, 0x93, 0x44, 0x01, 0xee, 0x31, 0xff, 0x31, 0xc0, 0xfc, 0xac, 0x84,

0xc0, 0x74, 0x07, 0xc1, 0xcf, 0x0d, 0x01, 0xc7, 0xeb, 0xf4, 0x39, 0xd7,

0x75, 0xdd, 0x67, 0x41, 0x8b, 0x5e, 0x24, 0x44, 0x01, 0xeb, 0x31, 0xc9,

0x66, 0x67, 0x42, 0x8b, 0x0c, 0x53, 0x67, 0x41, 0x8b, 0x5e, 0x1c, 0x44,

0x01, 0xeb, 0x67, 0x8b, 0x04, 0x8b, 0x44, 0x01, 0xe8, 0xc3

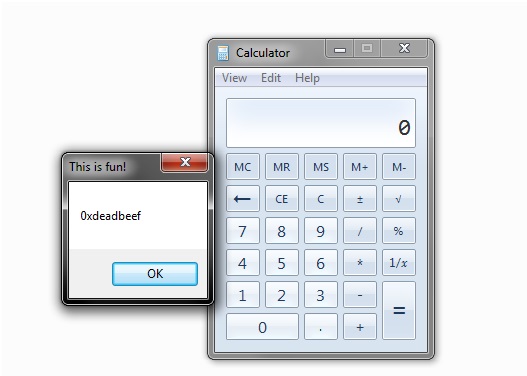

};

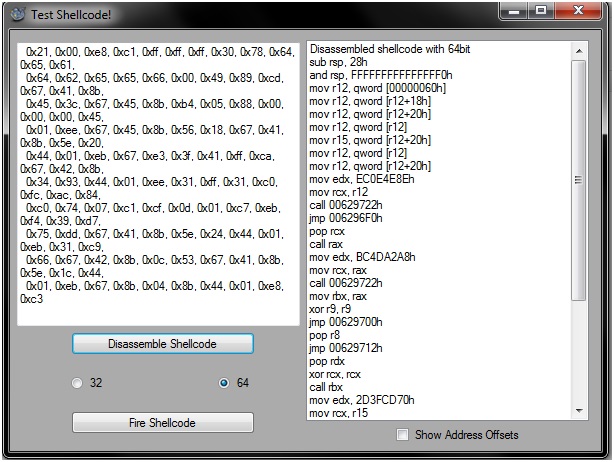

unsigned int messageBox64bit_sc_len = 258;Taking all of the hex bytes returned, let’s go to another little program I wrote because I wanted to be able to fire shellcode against a target, calc, to make sure it would work in a remote process. Please note this application is still in more or less of a beta form and I mostly wrote it because I wanted to play around with an open source disassembly project, BeaEngine.

Fire up the application, insert the bytes into the left text box and selected the assembly version we are using (x64). Afterwards, hit the disassemble button and the disassembly will appear on the right. I do this to make sure that the assembly is still intact and because I wanted to be able to recover undocumented shellcode that I had (opps).

Afterwards, hit “fire” and the application will run “calc” and inject a thread into it which will run the shellcode.

Success!

EOF

I hope that this blog post has helped in aiding the development of Win64 shellcode… I am just getting started with writing what I have learned in my research and am hopefully going to continue to write/document on my website.

To download the applications I used I have zipped them up here: Resources

Update 3/18/2015: I have open sourced my shellcode Tester and put the repository on my github page here.